- Home

- Frank Richardson

The Mayfair Mystery Page 11

The Mayfair Mystery Read online

Page 11

‘“That is impossible,” said Johnson. “If there were only one impi of Zulus in Mayfair, the police would certainly hear of it. Even the Intelligence Department of the War Office would get to know of a foreign invasion of the Metropolis.”

‘Then they all helped one another and worked. I got tired of watching them work. My home—or, rather, the place where I used to live—looked as though an auction had been held there.

‘The detectives remained all day. I helped them —as much as a layman could—by going out and getting tinned meat and cheese, and whatever other food they thought they could detect on best. In fact, I became a sort of handyman to the Force. One young detective to whom I hadn’t been introduced took me for the caretaker and spoke rather harshly about my incivility. My friend Johnson corrected him. He is really the best all-round detective that I have met. Though the house was packed with people, more continued to come in. I opened tin door to a young man who said he wanted to enlist, and thought that this was a Yeomanry recruiting-office.

‘I said I was hanged if it was. It used to be an Englishman’s castle; but now it was a home for lost detectives. He said he’d just as soon be a detective as a Yeoman. So I let him in. I daresay he helped.

‘When I got time, I, too, helped. For example, I asked my friend Johnson if he knew of any recently-married burglar who owned a refrigerator.

‘Johnson went through Barlow’s list, but couldn’t find one. He said that, as a class, burglars did not buy refrigerators.

‘My idea was that some young burglar who had just married, and had got a refrigerator as a wedding present, had completed the rest of his furnishing arrangements by removing my stock.

‘Barlow said there was nothing in the idea.

‘Johnson was with him. There are moments when Johnson is positively Barlowesque. So I didn’t think it prudent to say anything about the gentlemanlike person with red whiskers. It was my burglary, and I had a right to express my views, but I reserved that right.

‘Later Johnson said: “The thing to do is this. I will call the officer who was on point duty outside the house last night. He is one of the cleverest men in the Force. Your goods were removed last night, because I saw them here myself at five-thirty-seven.” Barlow made a note of it at my direction. “And your goods are not here now. Make a note of it, Barlow; they are not here now. Assume my hypothesis to be correct, and that your goods were removed in the night, an intelligent officer who is on duty outside your door must have noticed something. I don’t say what, I say something; possibly the removal of your goods.”

‘The officer was sent for.

‘He knew all about it and readily described the whole occurrence.

‘At half-past ten the night before, three furniture-vans had driven up to the door, and, having been filled with the things that I used to own, had been driven in the direction of the North of London, or the North of England—he couldn’t say which.

‘Johnson complimented the officer upon his intelligence and accuracy.

‘“Did you notice anything about one of the men?” I blurted out. “Was he wearing whiskers at all—red ones?”

‘Johnson said that burglars never wore highly-coloured whiskers. They would attract observation.

‘“Did anyone connected with this removal speak to you?” asked Johnson.

‘“One of the men said it was a fine night,” the officer answered.

‘“Was it a fine night?”

‘“It was, sir. So the remark did not excite my suspicion.”

‘“Didn’t it seem to you suspicious that I should have my furniture removed in the middle of the night?” I asked.

‘“No, sir. I knew that you were well-to-do and kept your carriages and what-not, and paid all the tradesmen regular and the servants liberal. No, sir. I didn’t suspect you, sir, I’m bound to say.”

‘The more I looked at the idiot the more mysterious did his face seem to me. I am rather a judge of physiognomy, and I should say that the policeman was intended by nature for a window-cleaner—or, at any rate, that he had window-cleaning instincts.

‘Of course, this might have been accounted for by atavism.

‘“Besides, sir,” he added, “the man said that you had been suddenly called away to go salmon-fishing in Norway.”

‘“Oh! Do you think that I go salmon-fishing in Norway with a grand piano and a billiard-table?”

‘Johnson corrected me kindly but firmly.

‘“It is,” he said, “no part of the duty of a constable on point duty to pry into the habits of respectable householders. We do not countenance the Continental system of espionage in ‘Merrie England’.”

‘Everybody murmured applause (except the Austro-Hungarian investigator).

‘The house sat till a late hour that night.

‘Next day I received a black pearl and diamond scarf-pin. It came by post, anonymously. Presumably it was the gift of some woman sympathiser who knew that my sister was out of town.

‘Black pearls enable the wearer to penetrate the most secret mysteries. This one didn’t help me one per cent, with my burglary. But, somehow, my wearing it helped my sister. She came home from Monte Carlo in a bad temper, and got all the servants back, made me apologise to them, re-furnished the house out of the burglary insurance money, and caused the cook to confess that she was engaged to marry the intelligent policeman on point duty, who hated being in the Force, and remained in it only because she liked to see him in uniform, but cleaned windows better than anyone in England, he being, as you might say, born and bred in the profession, his father having cleaned windows at Buckingham Palace itself with his own hands, which she would have told before only nobody hadn’t asked her, and she gave him the job when off duty, as the saying is, the Window Cleaning Company only sending people to break windows and not to clean them, in a manner of speaking.

‘Of course, Alice meant well when she arranged, by way of a surprise, to have the black pearl substituted for the opal in my scarf-pin. She says that it is not manly to rely on outside help to ensure the efficacy of one’s prayers, and that an opal is a vulgar stone, whereas a black pearl is deep mourning.

‘It certainly does clear up hidden mysteries in a business-like way. But it doesn’t explain why my sister doesn’t like Johnson, nor what that man did with his whiskers when he removed my furniture on that singularly fine night. Still, you now thoroughly understand the futility of trusting to Messrs Johnson and Barlow.’

CHAPTER XX

JOHNSON BECOMES BRIGHTER

WHEN he had finished, the house was against him. Said Sir Algernon:

‘You only told that infernally rotten story in order to introduce the subject of whiskers. You’re mad about whiskers!’

‘Good heavens!’ replied the novelist, ‘we’re all mad about something; and whiskers are quite the sanest things to be mad about. At any rate, it is better to talk about them than to wear them. You, Sir Algernon, are always wearing them: I’m not always talking about them.’

Several voices from the middle of the table:

‘For Heaven’s sake, shut up about whiskers.’

With intense politeness Robinson turned to Harding:

‘My dear Harding, this instructive anecdote will, I trust, completely prove to you the futility of believing in Johnson. Even without Barlow, I doubt whether Johnson would be of the slightest use.’

The K.C. answered:

‘You may be surprised to hear that, as a matter of act, Johnson is on the track of this girl.’

He had, in the days when a Junior at the Old Bailey, had a very considerable experience of Johnson. He did not consider Johnson by any means a fool. Still, of Johnson’s efforts in the Mingey case he would not have spoken at the Gridiron Club but for Robinson’s attack upon that eminent detective. That very morning, certain events had occurred which he described in detail to the listening members.

This is what had happened.

Harding was sitting in his chambers at nine-thir

ty, as usual engrossed in his work, when Mingey entered with wild, staring eyes. Since his daughter’s disappearance, he had grown infinitely more cadaverous. His hands were shaking. In a quivering voice he said:

‘Oh, sir, there’s news of my daughter! She has been seen.’

The K.C. expressed his delight.

‘Then she is alive! That’s good hearing. But, excuse me, Mingey, I’ve got this case to get up. We will talk about that afterwards.’

‘If you could do me a great favour, sir, I should like you to see Inspector Johnson, who is here. Besides, we shall not be on in Court 5 before the adjournment. It would be doing me a great kindness, sir.’

Mingey had been a faithful servant. It was a matter of vital importance to the clerk.

‘Let the Inspector be shown in.’

The detective entered, bustling and business-like.

He explained that he was anxious to place the facts which had come to his notice before the K.C.

‘You, sir, have had a great deal of experience in criminal matters, and owing to your friendship for a gentleman whose name figures in this case you may be able to throw some light upon it.’

‘I will do anything I can, Johnson. Is Mingey to stay or to go?’

‘Oh, let him stay, if you please, sir.’

Then Johnson told his story.

He told of how Nellie, the servant-girl, had gone to Vine Street police-station, how he had interviewed her, and how she had identified the photograph of Miss Mingey with the woman who had helped Sir Clifford Oakleigh, while in a drunken condition, into a cab. He repeated from P. Barlow’s notes his conversation with Sir Clifford’s valet. He stated that he had used every effort to see the celebrated physician but had failed. He added that the movements of Sir Clifford Oakleigh were extraordinary. ‘He comes and goes in a most mysterious manner. I don’t know whether he bribes my men who are on the watch or not, but, at any rate, he enters and leaves the house without their seeing him.’

‘Really!’ exclaimed Harding, ‘you don’t mean to say that you suggest Sir Clifford Oakleigh has anything to do with the disappearance of Miss Mingey?’

‘The moment has not yet arrived for me to draw any conclusion. I am completely baffled. But you know Sir Clifford Oakleigh well?’

‘I know him well enough to know,’ said the other hotly, ‘that his character is beyond reproach.’

The clerk interposed.

‘My daughter was very grateful to him for what he did for her. You know, Johnson, he completely cured her of a nervous trouble.’

‘Look here, Johnson,’ said the K.C., ‘I haven’t lately done much in the way of criminal work, but years ago I used to see a great deal of you at the Central Criminal Court, and also at the North London Sessions, and it always struck me that you were a discreet officer. It is not discreet to make a fantastic charge against a man who is at the head of his profession.’

‘I repeat, sir, I make no charges.’

‘But the innuendo!’ cried Harding. ‘Undoubtedly you are making an innuendo, and it’s the most remarkable innuendo that I’ve ever heard. A doctor, one of the most respected doctors in the land, is connected—with all respect to Mingey, who is the best fellow in the world—by a girl who is not of his own class. In an incredibly short time their acquaintance ripens to such an extent that he becomes intensely alcoholic in her company, and she takes him off, Heaven knows where, in a four-wheel cab.’

‘Ah,’ said the detective, ‘but we do know where she took him. We have traced the cabman. Cabmen, as a rule, are very hard to trace, but we’ve got this man.’

‘Where was it?’ exclaimed Mingey.

‘To No. 69 Pembroke Street, Mayfair.’

‘Good Heavens!’

Johnson supplemented: ‘That house belongs to Sir Clifford Oakleigh.’

‘But he has let it to Miss Clive,’ interposed Harding.

‘Do you know Miss Clive, sir?’

‘Certainly I do.’

‘Well, the fact remains that he and Miss Mingey went there that night.’

‘That isn’t possible,’ answered Harding. ‘Miss Clive doesn’t know Sir Clifford Oakleigh. Although she is his tenant, she has never met him. It’s extraordinary, I admit, but it is so.’

The detective smiled incredulously.

‘Do you know that for a fact, sir?’

‘I had it from her own lips. She has never met him.’

‘I will make a note of that. That is what the lady herself said.’

Harding struck the table in annoyance.

‘You don’t mean to say that you’ve been poking your nose into her house.’ Here indeed was infernal impertinence. Why should the woman of women be annoyed by the police?

Apologetically Johnson said that he had only made ‘ordinary inquiries.’

‘Yes, but, Johnson, don’t you understand that ordinary inquiries are extraordinary to a young girl? You surely don’t suspect that she had anything to do with it? You will never make head or tail of anything, Johnson, if you believe the evidence of cabmen and servant-girls.’

‘Well, sir, we can’t get our evidence from Prime Ministers and Archbishops.’

‘What is your evidence now you’ve got it? To me, it amounts to nothing. It is more than likely that these two people were mistaken. There is a reward offered, and anybody will make up some cock-and-bull story for the sake of a reward. This is the most cock-and-bull story I have ever heard. Cock-and-bull! Why, it’s a farmyard and ranch story! And to make it at all possible you have to invent a theory that a man in the position of Sir Clifford Oakleigh bribes your plain-clothes men in order to move about surreptitiously with a patient whom he has only seen once or twice!’

Very gravely Mingey interrupted.

‘No, Johnson,’ he said, putting his hand firmly on the Inspector’s shoulder, and there were tears in the red rims of his eyes, ‘my daughter is not that sort. She has never gallivanted. She was always took up with her reading and her Sunday School. Neither my wife nor I hold with putting a lot of fal-lals on a girl. But ever since she has disappeared, my wife has often said to me, not once nor twice but twenty times, “If Sarah had taken more trouble with her dress, she would have been a pretty girl,” but she did her hair nohow, and that’s the truth. Not that it would have mattered a bit if she had made herself look pretty. She would have disappeared all the same, only more so.’

‘I take your meaning,’ replied Harding, with a nod.

Though pressed by the detective, neither by reason of his own criminal knowledge nor his knowledge of Clifford Oakleigh, could he throw any light on the matter. He could not help, and the interview terminated.

These facts he placed succinctly before the listening members of the Gridiron. Around the table were seated two Treasury Counsel, the leading expert in medical jurisprudence, and a writer of detective novels whose fame is world-wide.

‘Can any of you men help?’ he asked.

For two hours they discussed all possible theories, but when they parted no satisfactory conclusion had been reached.

CHAPTER XXI

NEWS OF SARAH

‘I DON’T know what has happened to you, Mingey,’ said Harding, ‘you seem to have lost your memory. I told you to watch Appeal Court II this afternoon, and you were not there.’

The shambling clerk expressed his regret.

‘Oh, that’s all very well, but these things are important. You knew that I could leave the King’s Bench whenever I was wanted. What’s the matter, man?’

Mingey made no answer, but rubbed his thin hands together.

‘I make every allowance for what you’ve gone through,’ said the K.C., ‘but believe me, the only way to escape from a sorrow is by attending to one’s work.’

‘I’m very sorry, sir.’

‘I’m sure you are.’

But he could see that the clerk was desirous of saying something to him. He sat down at his table, threw a cursory glance over the briefs that lay upon it, untied the red t

ape that surrounded one of them. Then, without looking at Mingey, he asked, in an apparently offhand tone:

‘Is there any news about Sarah?’

‘Yes, sir, there is. That’s what it is. I’ve seen her.’

‘Seen her?’ But he did not look up from his papers.

‘I saw her last night, sir.’

Harding dropped the blue pencil with which he had prepared to mark the brief, and leaned back in his chair.

‘Last night!’

Mingey took a step forward.

‘Last night, sir, as I’m a sinner: last night, sir, as I’m a Christian, I saw her with my own eyes.’

‘Where? Where?’

With wide-open, sightless eyes the clerk answered:

‘Coming out of the Prince of Wales’ theatre.’

Harding looked in astonishment at him.

‘You in the neighbourhood of a theatre!’

Mingey explained.

‘I had come from a meeting of the Particular Strict Baptist Benefit Society, and I was walking to a ’bus. I was just outside the Prince of Wales’ Theatre when the audience was coming out. It was raining. I hadn’t got an umbrella so I stopped for a minute under the portico. And I saw her. She was with a gentleman and a lady. She was laughing and talking. You won’t believe me, sir, but I tell you this, she seemed a sort of glorified version of my Sarah. She was splendidly dressed, silks and laces and diamonds, and her hair all waved.’

Then he staggered to a chair and buried his face.

‘Oh, my God, my God,’ he sobbed, ‘that she should have come to this!’

Harding rose, and tried to console him. He patted the quivering old man on the back. But he sought in vain for words of comfort. The best thing he could find to say was, ‘Well, after all, it’s a great thing to know that she’s still alive.’

The lean, lank man sprang up erect.

‘A comfort!’ he cried, ‘to know that my daughter is a gay woman! That’s what she is, a gay woman. A comfort! Oh, sir, I have served you all these years. I have been faithful to you. And this has happened to me in my old age. She was a girl I would have trusted…as I trust you, sir.’

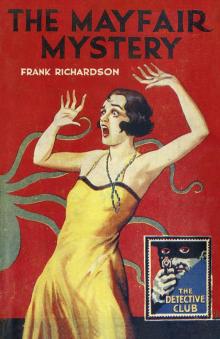

The Mayfair Mystery

The Mayfair Mystery